The Church and Disaster Relief

Disaster relief is a complex thing.

See Fred Johnson’s Essay, “Fallen Humanity and Wall Street: Disasters of ‘When’ not ‘If’“

See Jose Irizarry’s Essay, “Disasters, The Poor, The Rich, and the Church”

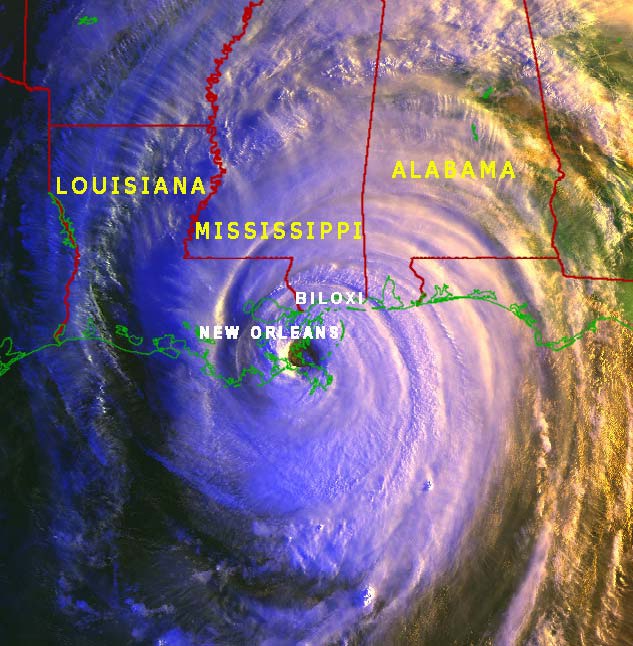

On the fifth anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, the American public had many opportunities to reflect on the flooding that enveloped not only New Orleans but much of the Gulf Coast in August 2005. At least two things became clear in the reports: Katrina was horrific to a level not imaginable before the storm, and much of the damage wrought by the storm and the subsequent break in the levees may never be addressed adequately to effect recovery.

Disaster relief is a complex thing. For those governments able to offer aid, political considerations come into focus; and for governments trying to address a domestic crisis, there are also issues on the table. While it didn’t make much news at the time, nearly 100 countries offered aid to the US in the wake of Katrina – some of which was refused. This is not a singular case; refusing aid is relatively common. Reflection on the impact of taking assistance – and incurring something of a debt – to political adversaries regularly gives governments pause. Other factors affect decisions, and eventual outcomes, of disaster relief as well.

Understandings of poverty have an impact on whether and how aid is offered.

Understandings of poverty – of poor people and why people are poor – have an identifiable impact on aid that is offered. Politicians and legislators look for public support of the decisions they make, and often, popular understandings of poverty discourage aid. Barbara Bush’s suggestion after Katrina that the crisis was “working well” for the underprivileged received a lot of coverage. It echoed some popular opinions of the poor, largely Black victims of the crisis, as well. A sense of how victims stand up to their responsibilities, and beliefs about whether people “deserve” aid, come to the fore here.

A sense that governments will mismanage aid also decreases popular support. Much of the reporting on the January 2010 earthquake in Haiti noted the country’s status as the poorest in the western hemisphere, and a history of corruption in the country; articles analyzing the possibilities of “success” made note of these realities and predicted dismal outcomes.

Finally, perceptions of the religion of affected populations play a role. Racism and fear of or distaste for the beliefs of victims challenge the will to help – and the perceived goodness, or lack of same, of one’s government offering assistance. Relief for victims of the flooding in Pakistan is a case in point. Calls to send money through text message netted 32 million US dollars within days of the earthquake in Haiti; weeks after a similar call went out about the flooding, only $10,000 had come in. Analysts cite feelings about Islam as a primary factor in this lack of response.

Challenges to Disciples in Disaster Relief Work

A number of challenges arise in this narrative for we who worship and serve Jesus of Nazareth.

First, the race and religion of victims are non-starters in a Christian view of disaster relief. Despite press understandings of “Christian values”, following Jesus forces a non-partisan approach to those who are suffering. How do we as Christian leaders move people toward a more faithful stance toward the other? Prayer, Bible study, and good preaching are among the effective tools at our disposal.

An awareness of history is also required for those who would follow. There are reasons why poor people are poor, and poor nations are poor, that get right into our comfort zone – and can affect our comfort. Haiti’s origins, and US government participation in keeping the nation poor to serve geopolitical ends – both in the 19th century and in this decade – are well-documented. The continuing travail in New Orleans and along the Gulf Coast is due to long-established government neglect of the needs of the people there, sacrificing them for the needs of the oil industry, a practice that continues as this sad anniversary is remembered. Carl Pope of the Sierra Club likens this to treating the region as if it were the US version of the Niger Delta; and Ben Jealous, president of the NAACP, reminds us that the practices of ecological devastation that quicken and deepen global climate change fall most heavily on communities across the globe that are poor and have a majority of dark-skinned residents, including New Orleans. This is because they have less power, of course, than the oil industry. And for those of us who live in a more comfortable, less risky area of the world than the 9th Ward of New Orleans, we are able to live there because we have more power too.

We who follow Jesus cannot plead ignorance when information is readily available, and we cannot abdicate responsibility for the powerless. For leaders, it can increase discomfort substantially to remind people of the truth – particularly when the truth includes criticism of the government or of industry – both of which can be perceived to put jobs at risk. Our current and past practices have imperiled and damaged many who are powerless. Amending those practices is the response of faith. Seeking for both alternative energy sources and for ways to lessen consumption of oil is also needed. Telling the truth about what happened and what is still happening is obligatory, no matter how uncomfortable it makes us.

Finally, worship and service of the Triune God includes perseverance in advocacy for justice and the giving of assistance to those in need. Governments will continue seeking to offer assistance in ways that are politically expedient. There will always be governmental goals that could be served or harmed by offering aid; in the current flooding in Pakistan, calculations are being drawn in the halls of power, and this will continue. The church needs to be in another place. Many communions, including my own, field staff and offer resources once disaster hits. As the economic crisis continues, however, resources dwindle and commitment can be attracted to other needs considered more pressing. Standing with people in crisis is definitional for the Body of Christ. This is not a responsibility we can afford to ignore.

Coming on Wednesday, October 13: Fred Johnson and Jose Irizarry join the conversation.

See Fred Johnson’s Essay, “Fallen Humanity and Wall Street: Disasters of ‘When’ not ‘If’“

See Jose Irizarry’s Essay, “Disasters, The Poor, The Rich, and the Church”