Why We Wait, and How Not To – by John Senior

Many of us don’t know how to be good citizens.

Many of us don’t know how to be good citizens.

One of the emerging media framings of Saturday’s tragic shooting in Arizona points to the excessive use of violence in our political discourse. Rep. Gabrielle Giffords was herself concerned about the crosshairs image that Sarah Palin’s political action committee used to represent the targeting of Giffords’ district for electoral defeat. Whether or not a meaningful causal link exists between violent political rhetoric of this sort and the attempted assassination of Giffords and the murder of six other people, including a federal judge, a 9-year-old girl, and one of Giffords’ staff, remains to be seen. But the interpretive framing is, it seems to me, right on. Many of us don’t know how to be good citizens. What we have instead is impoverished forms of political engagement.

When I talk about “us” and “we” here, I invoke my own experience. Whenever I think of what democracy in America is like, I instinctively recall my hometown, West Chester, Ohio, and the ordinary citizens who populated it. I think of the citizens of West Chester just because, I suppose, I knew them first and best. I understand, of course, that our political life is much more complicated. But the people of West Chester — mostly white, mostly wealthy, mostly conservative, consummately suburban — are also disproportionately powerful. They have a lot of money, and their congressional representative, John Boehner, is the newly elected Speaker of the House. To the extent that politics is about power and influence, the people of West Chester are worth thinking about. The rest of us will have to listen to them, whether we want to or not.

In West Chester, government should be limited. Taxes should be modest. “Small business” is an ideal, but businesses are rarely small. Social justice is charity. Racism mostly exists in the South. The socially marginal are lazy. The city (Cincinnati, in this case) is a suspicious moral space. Freedom is being left alone. Good citizenship amounts to voting in elections. Transportation happens in large vehicles on roads and highways. Global warming may not exist. Churches are social clubs. Political ire is raised when an economy of extreme privilege falters. In West Chester, in short, the free market norms political life.

Diagnosing the poverty of democratic politics in America

This last point is decisive, it seems to me, for diagnosing the poverty of democratic politics in America. In too many political spaces like West Chester, the market determines what good politics is about. When the market determines what good politics is about, most citizens are either disengaged from or poorly engaged in political life. Citizens are disengaged when enough of them think that they’re economically secure (although many, of course, are not). In that case, the market stifles political concerns under the weight of good times. Citizens in good times are politically slothful. On the other hand, citizens are politically engaged when enough of them don’t think that they’re economically secure. But in that case, they are out of practice, and so they don’t practice citizenship very well (in fact, they’ve likely never practiced good citizenship at all). Citizens in bad economic times are politically inept.

In lean years, many citizens think they can vote their way back into a bull market. Many of us wait for political elites to do the work. But many elites are also poorly trained in the virtues of good citizenship. In short, very few of us know how to work with others first to determine and then to achieve a good society, because a market-driven politics doesn’t encourage cooperation for the common good. Thus, we are liable to have politics of the vicious sort we have now.

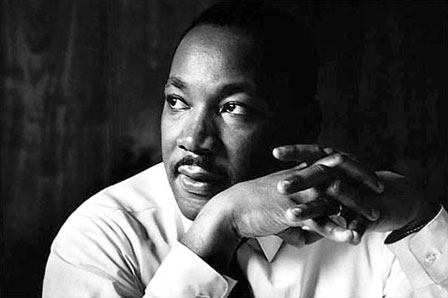

King’s moral formation as a whole political self

As I read again Dr. King’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” my thoughts turn to the challenge of good citizenship in disordered political spaces like West Chester. What strikes me first is that King knows how to make a good public argument. He knows that not just because he was well educated, but also because his argument, in this case written on the margins of scrap paper in a prison cell, flows from the experiences of injustice and the disciplines of resistance that train the heart, mind, and the body all to argue for justice in a concerted way. Good public argument, in other words, is written first onto, and then out of, the whole self, which is well trained in the habits of good citizenship.

Many political theorists and theologians who care about the place of religion in political life miss this key point. They think that political engagement in a democratic republic is mostly about skillful public argument. They’re right. But skillful public argument isn’t just a rhetorical problem (about the form of argument) or an epistemological problem (about the status of fundamental beliefs that motivate arguments). Rather, it is finally a question about the moral formation of a whole political self. The rigors of patient, intentional political training of the sort King describes in his “Letter” are prerequisite conditions for the formation of good citizens (what I would call “good citizenship”). They are also prerequisite conditions for those who wish to participate in meaningful public discourse of the sort King’s “Letter” represents – a far cry from the vitriol that passes for public debate today.

Hidden, and Public, Transcripts

While I’m on the point about public discourse, I should say that I agree with Dr. Holder Rich’s claim in her essay in this edition of Ecclesio that we ought to appreciate the way King brings the resources of his own religious and cultural tradition, a kind of “hidden transcript” from the perspective of dominant cultural powers, to bear on the problem of racial justice. But I wish to note that this is only part of the equation. King continually appealed, as he does in the latter half of the “Letter,” to a script in full public view – indeed, the most publicly accessible political script we U.S. Americans have. This script that frames the documents of the American founding, and at its heart is “the promise of America is freedom,” as King calls it, a promise unredeemed in the case of those who struggled for freedom in Birmingham. King goes on to say that, “We will win our freedom because the sacred heritage of our nation and the eternal will of God are embodied in our echoing demands.” The intersection of these complex traditions of moral meaning must be held in view if we’re to understand King’s project aright.

I am impressed, secondly, with King’s insistence that justice is finally about the kind of persons a political society makes. Does a political society and its laws enable human flourishing or not? For King, human flourishing is bound up in an “inescapable network of mutuality,” a “single garment of destiny.” A society that segregates persons from one another is sinful, precisely because, King argues, following Tillich, sin just is separation.

When our political culture is oriented to and by the market system, separation is normal.

It seems to me that when our political culture is oriented to and by the market system, separation is normal. When separation is normal, it becomes difficult for citizens to make sense of the relational quality of justice. Injustice and its remedy are framed primarily as transgression and retribution. Solidarity is relevant only when individuals are under attack. One hears this point of view in John Boehner’s own condemnation of the Arizona shootings: “An attack on one who serves is an attack on all who serve.” That is, it seems to me, a far cry from King’s “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

If we’re to get beyond a politics of separation, malaise, and incompetence, in which the material good of individuals is the only meaningful criterion, then we need to read King’s “Letter” more carefully, imagine the kind of political self it contemplates, and respond with the whole of our lives. With King, I am disappointed that the church, especially the church in places like West Chester, hasn’t always taken a more active role in forming citizens capable of a more expansive, relational politics, as the church is well equipped to train good citizens. My hope is that the church won’t wait to take King’s call, and God’s call, more seriously.