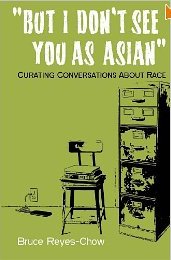

“But I Don’t See You as Asian”: A Conversation with Bruce Reyes-Chow – Part One

Director’s Note: This week, our conversation is about Bruce Reyes-Chow’s 2013 book But I Don’t See You as Asian: Curating Conversations on Race. Today and tomorrow Bruce and I discuss issues raised in the book.

Director’s Note: This week, our conversation is about Bruce Reyes-Chow’s 2013 book But I Don’t See You as Asian: Curating Conversations on Race. Today and tomorrow Bruce and I discuss issues raised in the book.

Cynthia Holder Rich – You say we must commit as communities and as a country to talking about race. I agree with you and I wonder who it is you are targeting with this statement? That is, in your experience, are there communities talking about race? Are there internal conversations or cross-community conversations you know about?

BRC – My targeting with this book is not as much about the “who” should be talking as much as it is the “how” we could be talking. Other than NOT targeting hard core academics or the streetwise activities – both of whom we need – my hope is that this book is read by people of all stripes, so that it might spur a different way of talking about race and ratchet down the automatic defensiveness and demonizing that so often accompanies these personal and passionate interaction. And while I attempt to use humor and the sharing of my own foibles, I am in no way trying to lessen the importance of standing up to racist actions. On the contrary, it is my hope that people, by having a little more empathy and understanding, can transform that righteous indignation into social transformation be it at school, in the workplace or among family members.

As far as specific groups of people or conversations, I think there are always conversations happening that have the intention of shifting understandings of race. Some are driven by legislation while others by incidents that need to be addressed. And while these kinds of conversations are important, I think this book is best served around a table with friends, between a small group of trusted colleagues or alone simply in search of a greater understanding about why some words mean different things to different people.

CHR – If conversations were to occur, what outcomes would you expect or hope for?

BRC – World peace.

One of dangers that is present when people hold events or gatherings that are focused on race is that there is an inherent hope that we “solve” something at the end. Now I doubt many people are as naive to think that one gathering or even a six-week small group will alleviate centuries of racial interactions in the United States, but that doesn’t mean we don’t secretly hope it does.

To really get at the heart of racism and its manifestations in institutions and structures there will need to be legislative action as well as some people just agreeing to be pissed off about things, but living with change without attempting to destroy the systems themselves.

But along with these kinds of actions, I also think that a genuine shift in race relations will take more people just sitting down in settings where questions can be asked without judgment and emotions shared without fear of trying to be fixed. At the crux of this book is my belief that by having these kinds of interactions and conversations by more people, we can move the tone and nature of conversations about race towards deeper understanding and appreciation and away from further division and judgment.

CHR – Your title But I Don’t See You as Asian – that’s something very few Asian people would say, right? Is this a clue that you are writing for and to white people?

CHR – Your title But I Don’t See You as Asian – that’s something very few Asian people would say, right? Is this a clue that you are writing for and to white people?

BRC – Oh the title . . . this title thing is very interesting. I mentioned a bit at the end of the book that I changed the title a few times before landing on, “But I Don’t See You As Asian.” Right off, there were folks who thought it was better than previous ones and others who shared that it might make the book feel “too Asian.” In the end I went with the one that felt best to me and being who I am, while I do not think that it is too Asian, I suspect that it’s MORE Asian than folks are used to when talking about race today.

In regards to the “who” to whom I was writing, I think there are plenty of places of overlap, but if pressed, I would say it’s about 75% to White folks and 25% to People of Color. I run a danger in a few of the chapters of airing the proverbial “dirty laundry,” but I think it’s important for people of color to acknowledge our own internal “isms” that exist. This lets no one off the hook, but hopefully people can begin to find some commonality and extend some grace towards others who are also struggling with issues of exclusion.

While I do hope that many people will be able to get much from this book, I think an ideal place for this would be on a college campus where people are coming together in possibly a more ethnically diverse setting than ever before. Not only does this provide some pre-emptive filter building tools, but for People of Color, it might offer some language to express and/or understand their own experiences of race.