Confessing Truth

Hester Prynne has come to mind a lot lately. Hester, hero/anti-hero of The Scarlet Letter, lived in a time when people’s lives were constrained and restricted and their actions rigidly controlled by social norms supported by religious authorities. These controls lay differently on different characters in the book. Specifically, those with privilege (read land-owning white men) experienced the penalties of straining against society’s controls differently than others. Hester, falling pregnant during her husband’s long absence, was not among those so privileged. Convicted, imprisoned, and made to wear a sign of her crime – also understood as sin by said religious authorities — she makes the sign into a thing of beauty and refuses to name her co-adulterer. Hester Prynne suffers much, yet goes on to become a symbol for integrity under pressure – and even faithfulness – while never conforming to sometimes-hypocritical religious ideals and ideas.

Hester Prynne has come to mind a lot lately. Hester, hero/anti-hero of The Scarlet Letter, lived in a time when people’s lives were constrained and restricted and their actions rigidly controlled by social norms supported by religious authorities. These controls lay differently on different characters in the book. Specifically, those with privilege (read land-owning white men) experienced the penalties of straining against society’s controls differently than others. Hester, falling pregnant during her husband’s long absence, was not among those so privileged. Convicted, imprisoned, and made to wear a sign of her crime – also understood as sin by said religious authorities — she makes the sign into a thing of beauty and refuses to name her co-adulterer. Hester Prynne suffers much, yet goes on to become a symbol for integrity under pressure – and even faithfulness – while never conforming to sometimes-hypocritical religious ideals and ideas.

Life informed by truth or by falsehood – these are foundational themes of The Scarlet Letter. Hester Prynne knew the central truth of the tale, the truth on which the story turned. Her very life was changed by truth or its lack. Armed with knowledge of the truth, she chose to unremittingly live by it, transforming not only her life but the lives of many others, and ultimately, the life of the community. Life informed by truth unmasks hypocrisy and transforms communities.

In the months since the 2016 US Presidential election, I’ve reflected on popularly-accepted religious ideals and ideas, on the pain of religious hypocrisy, and on truth – on religion and truth, particularly among white American-born Christians, who are among the privileged of our time. It is hard work, striving to discern the meaning of truth and religion in deeply and sometimes, even violently, polarized times, as people of faith stand ready to demonize each other when difference of opinion surfaces. The work is made more difficult with the realization that the election cut right through communities of people who claim fellowship in Christ and seek to follow Jesus.

As I write this, 134 days have passed since the election. New, or renewed, reclaimed, repurposed phrases – “alternative facts” – “fake news” – “the press is the enemy of the people” – “America first”, and “alt-right” – these have entered our lexicon, forming and informing our understandings and lives. These impact the ways we understand faith and truth. Combined with vocab we learned during the campaign – like “Muslim ban” – “lock her up” – “build that wall” – “p***y-grab” – these lead to the question: do these offer a picture of life founded on truth, truth that transforms for good?

You might think you know the answer, but the reality is that Christians in the US do not agree on how to answer this question. The President’s approval rating continues to drop, even among those who voted for him and still support him, but that has not led to harmony and the up-building of peace in Christian congregations and denominations. The reasons for this are many and diverse – here are a few of these.

While most would agree that oppression is happening in our nation, people who follow Jesus do not agree on who is being oppressed. A 2016 study of the Brookings Institution and the Public Religion Research Institute showed that almost ¾ of white evangelical Christians in the US see white evangelical Christians as more oppressed than other groups in the nation.

Additionally, news reports show that many conservative Christians are still happy with the President’s performance. Reasons for this include:

- His choice of a Supreme Court nominee that some believe will help build the voting bloc needed to overturn Roe v. Wade passes a key litmus test for many.

- Trump’s strong support for overturning the Johnson Amendment, which would result in allowing nonprofit leaders to openly support political candidates, sounds like support for religious freedom to some.

- And, even though it has been struck down by the courts, the plan in the first Travel Ban to view “persecuted Christians” as a protected minority lent support to the understanding that Trump had Christian values in mind as he crafted his Executive Order.

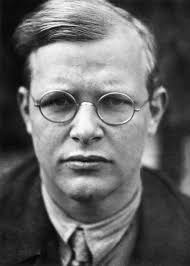

There are many Christians opposed to every one of the President’s actions and policies referenced in the last two paragraphs. The Christian church has always featured division. In our time the fissures in the body have become stark. This has led some to question whether we are at a moment like that faced by Dietrich Bonhoeffer in the 1930s, when he felt led to resist the Nazi takeover of the German Church. Stephen Haynes and Mark Edington are among those who have explored whether ”a Bonhoeffer moment” – a time when the Gospel is at stake, when Christians have to take a stand – has arrived. Others across the church in the US and beyond are also asking: has the moment come when we must confess? Are we at a status confessionis moment – a time when we must define and delineate what it means to follow Jesus, and then act on what we, aided and led by the Spirit, come to discern?

It might be that we are at this kind of moment.

If we are, it is folly to assume that if we get our confession right, divisions in the body will end. Bonhoeffer’s resistance was not greeted with praise, and many Christians in Germany and other contexts did not support his efforts. The development of new confessions can instigate deeper division – and even schism. Disciples of Jesus do not come to a moment of confessing to move toward harmony – but to move away from hypocrisy and toward the cross. If we are at a moment when the Gospel is at stake, it is because baptized Christians are among those who have come to accept racial hatred, misogyny, violence, and a budget proposal based on fear of the other and disregard for the least of these as truth. Stating this openly is not some sacred form of Dale Carnegie course[1], and we cannot expect to easily win friends and influence people through the endeavor. Those who preach Christ crucified must do so knowing the cost, something of which Dietrich Bonhoeffer had knowledge.[2] We who confess truth might hope to eventually come to help move the church toward a more truthful stance – a path that will undoubtedly feature pain, and possibly – at some point far in the future – deep joy as well.

If we are, it is folly to assume that if we get our confession right, divisions in the body will end. Bonhoeffer’s resistance was not greeted with praise, and many Christians in Germany and other contexts did not support his efforts. The development of new confessions can instigate deeper division – and even schism. Disciples of Jesus do not come to a moment of confessing to move toward harmony – but to move away from hypocrisy and toward the cross. If we are at a moment when the Gospel is at stake, it is because baptized Christians are among those who have come to accept racial hatred, misogyny, violence, and a budget proposal based on fear of the other and disregard for the least of these as truth. Stating this openly is not some sacred form of Dale Carnegie course[1], and we cannot expect to easily win friends and influence people through the endeavor. Those who preach Christ crucified must do so knowing the cost, something of which Dietrich Bonhoeffer had knowledge.[2] We who confess truth might hope to eventually come to help move the church toward a more truthful stance – a path that will undoubtedly feature pain, and possibly – at some point far in the future – deep joy as well.

It is also true that, as we discern together, in denominations, congregations, and in other groupings – even interfaith gatherings – that transcend boundaries, help is available to us in extant confessional resources. In the next post, I outline some ideas on how we might use existing confessions to move from where we are to a more solid footing on truth.

If we are at a moment when we must confess, the content of the confession will be of central importance. My final post this week begins to explore what I believe must be included for Christians, particularly white Christians, in the US at this moment. Spoiler alert: truth – confessing and understanding truth, as we follow One who claimed the name “Truth” (John 14:6) – this, for me, is at the heart of what cries out to be confessed. Like for the fictional hero of The Scarlet Letter, the outing of truth may hurt and hurt deeply, and it is the only way out of the wilderness in which we find ourselves today.

Cynthia Holder Rich (MDiv, MCE, PhD) is the founder and editor of ecclesio.com. Additionally, she has served in parish ministry, mission service, and graduate theological education and administration, and has published three books, many scholarly articles, and a number of curricula pieces for use in congregations. Since its launch in 2010, ecclesio.com has hosted conversations with over 600 pastors, scholars, activists, authors and leaders of the church from around the world.

[1] Dale Carnegie (1888-1955) was a self-help pioneer and developer of the Dale Carnegie Course, on which he based the book How to Win Friends and Influence People (1936), one of the first self-help best-sellers. The book is still in print and ranks 9th in sales on Amazon.com’s nonfiction books list. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/How_to_Win_Friends_and_Influence_People

[2] Dietrich Bonhoeffer, The Cost of Discipleship, 1937. Original title: Nachfolge