How Long? A Meditation for Holy Week by Cynthia Holder Rich

How long will it take? How long? Not long, for no lie can live forever.

Martin Luther King Jr., Montgomery, Alabama, March 25, 1965

How long, O Lord? Will you forget me forever?

Psalm 13, NRSV

It is Holy Week, a time of deep emotion for those who follow Jesus. It is a time for grief; for loss; for suffering; for contemplation.

It is a time for anger.

No really – Holy Week and anger are made for each other. The conviction of an innocent person, and the subsequent execution of that person we know to be innocent – these should, or could, bring us to anger. Right? But they do not – at least, anger rarely, if ever, finds voice in much of Christian worship. This is not due to a lack of capacity for anger among disciples. No – it is because anger is not an emotion that finds a comfortable home in much ritual practice. Anger is understood by many as destructive – damaging – unseemly, and even unholy, so not something that should be expressed during the very Week we call Holy. The expression of anger is unknown for many Christians in their understanding and practice of worship. So how, then, can we who follow Jesus faithfully respond to events that inspire righteous anger – be they the execution of Jesus, or the execution of other innocents?

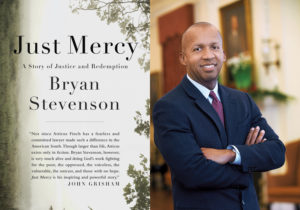

I’ve been reading Bryan Stevenson’s Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption[1] this Lent. Stevenson is the founding director of the Equal Justice Initiative, an organization that “challenges poverty and racial injustice, advocates for equal treatment in the criminal justice system, and creates hope for marginalized communities.” I first became aware of Stevenson’s work when someone shared his TED Talk from 2012 with me. Bryan entitled his talk “We Need To Discuss an Injustice”. The talk exposes the injustice in the ways in which the death penalty is used in the US justice system. Stevenson became conscious during a law school internship of the ways in which capital punishment is unevenly employed in the US, and the impact a person’s race, age, education, bank account, health or illness, and state of residence have on whether or not someone will be sentenced to death. The evidence offered in statistical analysis shocks, shames, and (should) anger:

I’ve been reading Bryan Stevenson’s Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption[1] this Lent. Stevenson is the founding director of the Equal Justice Initiative, an organization that “challenges poverty and racial injustice, advocates for equal treatment in the criminal justice system, and creates hope for marginalized communities.” I first became aware of Stevenson’s work when someone shared his TED Talk from 2012 with me. Bryan entitled his talk “We Need To Discuss an Injustice”. The talk exposes the injustice in the ways in which the death penalty is used in the US justice system. Stevenson became conscious during a law school internship of the ways in which capital punishment is unevenly employed in the US, and the impact a person’s race, age, education, bank account, health or illness, and state of residence have on whether or not someone will be sentenced to death. The evidence offered in statistical analysis shocks, shames, and (should) anger:

- 1 in 9 people on death row in the US are wrongfully convicted;

- African-Americans convicted are 11 times more likely than whites to receive the death penalty, and a full 22 times more likely if the victim is white.

- Some of the people sentenced to death or to life in prison without the possibility of parole were under the age of 14 when convicted.

- Many of the people sentenced to death or to life imprisonment are mentally ill. Their mental illness often increases as a result of their interface with law enforcement and the judicial system, and with the US penal system.

- An infographic developed by the National Registry of Exonerations, a project of the University of California Irvine Newkirk Center for Science and Society, the University of Michigan Law School and Michigan State University Law School, further illustrates. Research by Registry staff concludes that black prisoners are more likely to be innocent than white prisoners, for crimes ranging from murder, to sexual assault, to drug offenses.

These facts and the research on which they are founded put the lie to the philosophical foundation of “liberty and justice for all” which US schoolchildren reference while reciting the pledge each morning. Our understanding that the justice system is just – the backbone of what many Americans see as definitional for that idea we call America – if we cannot count on this to be true, what then? Would we be angry if this was not true?

Stevenson names capital punishment an issue of identity, impacting our understanding of the identity, the humanity, of those on death row – and of our self-identity. He argues that the question is not whether people deserve to die for their crimes – the question is whether we deserve to kill. After all, brokenness is part and parcel of the human condition – in Biblical terms, all have sinned and fallen short of the glory of God (Romans 3:23). How is it that we who are broken deserve to kill other broken people? How, when we factor in what we know about the fallibility of human judgment and the multifaceted sins of prejudice – how do we find the brazen will to continue in this belief and the practices it fosters? How does continuing this practice impact how we understand the identity of those caught up in the practice, be they people on death row, or prison staff, or legislators, or prisoners’ families and communities – and how does it impact how we understand ourselves?

The stories in Just Mercy offer stark, horrific and gut-wrenching glimpses of what happens much too often in the US criminal justice system. These glimpses are crucial for those who do not know people who have been convicted of capital crimes, or who don’t have a relationship or knowledge of anyone who has gone to prison. As of 2010, African-Americans made up 13% of US population but 40% of those imprisoned. Hispanic Americans were 16% of US citizens, but were 19% of those in prison.[2] Hence, those in the US who don’t know at least one incarcerated person are probably white. If you don’t know at least one person who has been sentenced to death – you are most likely a white person with very few, if any, relationships with people of color.

As I write this, the state of Arkansas is preparing to execute 8 death row prisoners in 10 days this month. The executions are to begin the day after Easter – immediately following the feast of the Resurrection of our Lord, the holiest day in the Christian calendar. The number and speed of executions will break records. The medications to be used in the executions are about to expire. Arkansas officials are hurrying to complete the killings before the buy-by date passes on the drugs they will use to complete the task. These drugs raise some issues – some of them have been found to much increase the suffering of those executed. These have not slowed the speed at which state officials are moving toward a great number of death days in a row. Post-traumatic stress among prison staff and communities will be significant and long-lasting, as it will be on the families and communities of those executed.

I wonder, as I reflect on and remember the execution of Jesus, what emotions this oncoming state-sponsored slaughter might inspire. Horror? Dread? Nausea? Fear? Or perhaps – just perhaps – anger? Would we be angry if we believed that of the 8, at least one had been wrongfully convicted? Would we become angry if we came to know that half of the eight men who are to die are African-American – and as research referenced here demonstrates, some of those men in particular are probably innocent? Would our anger – if we came to feel it at all – would it bring us to speech, or to action?

Bryan Stevenson, speaking of the despair that emerges in black communities from the crisis of mass incarceration and the unjust use of the death penalty, echoes the thought of Martin Luther King Jr. Dr. King knew much about anger and spoke plainly about its manifestation during US civil rights struggles, noting that “a riot is the language of the unheard”. Yet, Dr. King possessed optimism that “no lie can live forever”. But the lie of black and brown conviction that leads to the unjust and outrageously prejudicial racial makeup of the US prison population, and particularly of death row – this lie is alive and well. Can we bring ourselves to be angry about the lies in which we live, on which our system of “justice” is based? Can we allow ourselves to be moved by anger to act toward change?

Poet and philosopher David Whyte names anger as ”the deepest form of care, for another, for the world, for the self, for a life…for all our ideals”. Anger can create spaces for conversation toward change. Anger argues that life shouldn’t be the way it is; it claims good, and hope, and life for those who lack, naming these as a birthright for everyone. Anger at injustice is founded in belief that the identity of all of us, broken as we are, is that we are made in the very image of God. This truth demands justice for everyone created by God. In this Holy Week, may we who worship and serve Jesus and him crucified care sufficiently deeply about this truth that we are moved to anger for our brothers and sisters caught in unjust systems. May holy anger energize our work to name and unmask unjust, death-dealing lies, claim and affirm the power of resurrection, and move toward life.

Poet and philosopher David Whyte names anger as ”the deepest form of care, for another, for the world, for the self, for a life…for all our ideals”. Anger can create spaces for conversation toward change. Anger argues that life shouldn’t be the way it is; it claims good, and hope, and life for those who lack, naming these as a birthright for everyone. Anger at injustice is founded in belief that the identity of all of us, broken as we are, is that we are made in the very image of God. This truth demands justice for everyone created by God. In this Holy Week, may we who worship and serve Jesus and him crucified care sufficiently deeply about this truth that we are moved to anger for our brothers and sisters caught in unjust systems. May holy anger energize our work to name and unmask unjust, death-dealing lies, claim and affirm the power of resurrection, and move toward life.

Cynthia Holder Rich is the founder and director of ecclesio.com.

[1] Spiegel and Grau, New York; 2014.

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Incarceration_in_the_United_States