Public Theology as Modern Prophecy – by R. Ward Holder

As my colleague noted in the earlier posting this week, “public” has become an increasingly popular adjective to describe theological work. It may be that theologians are desperately seeking relevance – shouting to themselves that their words and thoughts are important to a broad consensus. Setting aside the dead-end to which that approach inevitably leads, the question is still useful, “What is public theology?” Or perhaps, “How is public theology different from other theological work?”

Certainly, there is a sense in which all theology is public. Anytime a human being makes the kind of truth statements that are the material of theology, the way that human looks at the world is transformed. One cannot say truthfully and meaningfully that God is love, and then deny the importance of love. If human beings are integrated creatures, all theology is public.

Yet in another sense, all theology is not public. Public theology seeks to make sense of Luther’s insight of the reality of the two kingdoms – that humans are simultaneously members of the Church, and of human society. Thus, public theology concentrates its efforts upon those issues outside the church. In fact, public theology necessarily takes on a prophetic mode of proclamation and analysis that stands outside of the Church, and outside of the Nation/Community/Public Square. Insofar as this is possible, the public theologian critiques both the Church, and the Public. That is why a theologian like John Calvin, whose doctrines might have extraordinary impact upon a nation or community, is not normally seen as a public theologian.

This insight must also be paired with another, that public theology is not the theology of the public religion. In fact, public theology is almost the opposite of the “theology of the public or civil religion.” Public religion (Ben Franklin’s term), or the more popular term civil religion, is the religion that a community or nation accepts implicitly (and sometimes explicitly). We see this in America when politicians called for America to reach its “manifest destiny.” We see it in the characterization of America as the “New Israel,” or the “Light to the nations.” Public theology does not work to support such a phenomenon. It may have the task of analyzing and decoding the ideas that support a particular civil religion. One can see exactly such a case in Reinhold Niebuhr’s 1952 classic, The Irony of American History. Niebuhr spent the first chapter working through the Jeffersonian and Calvinist bases of American conceptions of itself, and its place in history. But he expended that effort in order better to critique these foundations, not to build an American temple upon them.

The public theologian assesses not only the nation or community or society. The public theologian also takes on the Church. As Martin Luther King, Jr. stated in his Letter from the Birmingham Jail, he was disappointed with the church. He complained that many churches had commited themselves to an otherworldly religion that made an unbiblical distinction between body and soul, between the sacred and the secular. Before King, Walter Rauschenbusch in his A Theology for a Social Gospel, noted that the Church, while pronouncing its concern for the gospel, demonstrates its concern for its own power and authority. Writing in a similar vein, Reinhold Niebuhr wrote in The Christian Century in 1922, that the interests of the Protestant churches in America were aligned with those of the middle class, and only a change toward a prophetic stance could save the church’s claim to be the bearer of the gospel. The prophet never brings a message of God’s approval of the religious or secular community, and a series of theologians from Rauschenbusch to Allan Boesak and Nancy Pineda-Madrid have worked out the implications of that insight. In some cases, this even has led the public theologian to bear the wrath of ecclesiastical theologians for not working out more conventional theological topics.

The public theologian, then, holds up a mirror to the community and the Church, to show the sins and the foibles of both audiences, and their opportunities for better choices. To do this well, I absolutely agree with my colleague that engagement with other thinkers in other fields is a necessity. The task of the public theologian is NOT advanced by half-formed ideas that have come out of a cursory perusal of the headlines on some topic of general interest. Public theology demands the commitment to the truth that connects both biblical realities and the insights gained in other sciences.

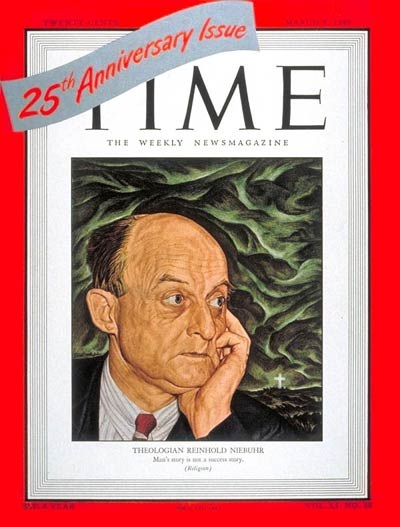

While there are significant figures who have done this throughout the last century, lately I have been concentrating upon the work of Reinhold Niebuhr. In part, that is for his currency – President Barack Obama has both explicitly and implicitly used Niebuhr’s thought. But in part, my fascination stems also from his courage. Niebuhr was willing to take on the most successful business man in the world, Henry Ford, at that height of Ford’s power and success. This might seem unremarkable in 2011, when liberal Christianity regularly and impotently bashes Wall Street. (see for instance Matt Taibbi’s “Why Isn’t Wall Street in Jail?” in Rolling Stone) But Niebuhr was a pastor dependent on the contributions of men whose livelihoods were determined by Ford, not an academic safely snuggled behind ivy-covered walls. Further, Niebuhr was just as critical of the Church, noting its complicity in the economic systems that committed such social sins. This stance cost him. By the time Niebuhr was working at Union Seminary, one account notes that there were only three churches in America that would invite him to preach.

Niebuhr’s example and thought have volumes to say to the contemporary situation. In a nation that blithely proceeds to war without counting either the cost or calculating the possibility of actually finishing, Niebuhr’s note of caution about the seductivity of easy answers must be heard. Further, in a society where popular Christian thought has been taken over by the prosperity gospel (Joel Osteen’s Become a Better You spent five months on the bestseller list), Niebuhr’s caution about confusing God’s will with humanity’s will-to-power is a necessity. If Niebuhr’s example is any predictor, it is unlikely that true public theology will gain a great popular following. But then, Jesus died alone.

Pingback: Public Theology, The Only Kind There Is – by Cynthia Holder Rich | Ecclesio.com