Poverty in the US – by Cynthia Holder Rich

Read Leslie Woods’ Essay, “Poverty in America and What the Church Can Do”

Read Karen Keene’s Essay, “Poverty in America and What the Church Can Do”

Where do the no-house people live?

In 1998, our family moved to Madagascar, which was generally understood at the time as the fourth-poorest country in the world. (Living under a coup government since 2009 has changed this status only for the worse, but that is a story for another day.) As the plan was for my husband and I to be able to teach theology in Malagasy, the first year was devoted to language study.

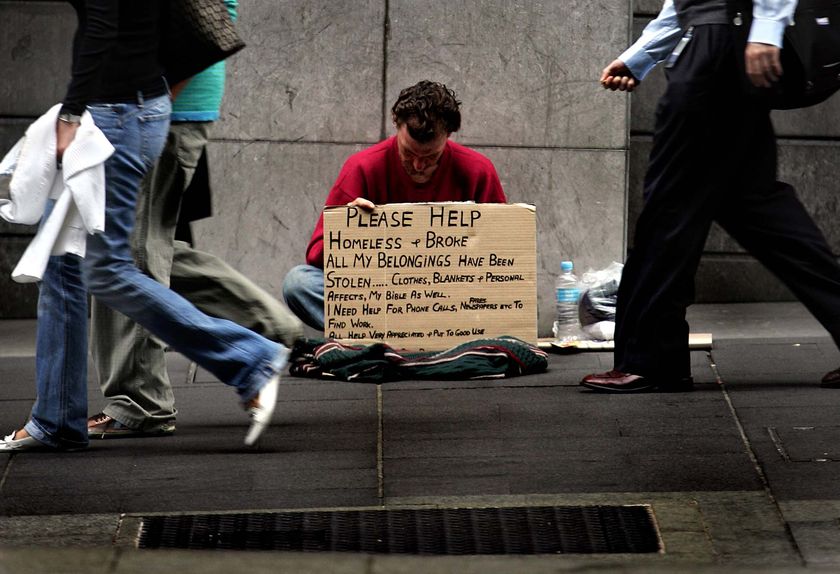

One day in language study (after the six-month point, as we were practicing conversation), I was slowly and painfully trying to find adequate words to discuss life in the US. My tutor had never been to the US, and her view was that life was wonderful there in that magical place. I was ready to say it was great – after all, after six months in a context very alien to my own, I was pretty homesick and open to the thought of running to the mall (a phenomenon that had yet to come to the island) most any day. I was also trying to indicate that it wasn’t all great – that some people struggled. I managed to say, as we looked in the book at pictures of American mansions, that some people didn’t have such nice homes. In fact, I said (literally in Malagasy), “There are no-house people in America.” There are homeless people in America.

My tutor smiled at me, a sure sign that I had made a mistake (again). Surely there are not, she said. She explained, slowly, that I must have used the wrong words. There aren’t no-house people in America. There are no-house people in Fianarantsoa (where we lived) and Antananarivo, the capital; but there AREN’T no-house people in America, because there is so much more money there. America is DEVELOPED and RICH, she said, slowly and clearly.

But I persisted. While I may have used the wrong words (and, I am happy to say, this was one early example of my use of the RIGHT words), I said, No, there really are homeless people in America. I really pushed the point, wanting to be clear.

And my tutor, a wonderful Christian Malagasy woman, after staring at me for a few minutes, said, “Nahoana?” Why?

Of course, that was back in 1998. Today, there are quite a few more no-house people in the US – or people who used to be “house people” – people with houses, who now don’t have houses. Poverty in the US has risen to staggering levels, to the point that the mainstream media has taken notice. The 2010 US Census found that 1 in 6 Americans live below the poverty line. Poverty during the economic crisis has hit those must vulnerable the hardest; those of vulnerable age and race have been impacted the most. While 22% of US children live in poverty, that figure rises to over 40% among African-American kids and over a third for Hispanic children. As the Occupy Wall Street protestors point out, the pain of the current crisis is not equally shared. Economist Jeffery Sachs and others note the problems created by the disappearance of the middle class in the US, a product of a complex history of policy developed to make wealth easier to amass for those on top of the economic scale that had the (perhaps unintended?) side effect of pushing more people out of the middle class.

Later this week, two who deal with these realities on a daily basis will join this conversation, offering more cogent wisdom and awareness of the facts than I can pull together. I turn, then, to what this means to followers of Jesus. Here, my statements find foundation in scripture and in the social statements of the Presbyterian Church (USA) and Pope Benedict’s 2009 encyclical, Caritas in Veritate (Charity in Truth). (A new Roman Catholic document, “Towards Reforming The International Monetary and Financial Systems In The Context of Global Public Authority”, was published since this essay was written. It came out this month from the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace at the Vatican. It is a very important document which calls for serious reflection, prayer and discussion by people of faith; you can view the document here.)

Poverty has been a main concern of published Christian social teaching for many decades. (In the Presbyterian Compilation of Social Statements , poverty appeared first in 1956.) This is not surprising, in that the One whom we profess to follow and see as Head of the Church talked more about money and its use than any other subject in his life on earth. As we consider the meaning and reality of poverty in the US, there are some important points to keep in mind.

- Poverty violates the humanity and integrity of those created by God and made in God’s image. Human life, as created and given by God, is sacred. This truth, while not contested in most Christian theologies, generally only emerges in arguments against reproductive rights for women. But a consistent ethic of the sanctity of life goes much further and deeper. It calls for respect for the personhood of all, and poverty (and all policy and practice which leads to poverty) violates this core principle of Christian faith. The Social Creed for the 21st Century of the Presbyterian Church (USA) names people “individuals of infinite worth”, and follows this with mandates for (among other things) protecting human rights, employment for all, and the right of workers to organize, and calls for hunger and poverty abatement programs as part of the responsibility of Christians.

In our time, gross levels of unemployment and underemployment have led to financial strain and poverty for many. They also contribute to a loss of identity, of a sense of personhood and purpose, and of shame. It is now a regular part of advertising copy announcing hiring to state that only those employed need apply. This suggests that people are unemployed through some fault, flaw or some error on their part, and thus being unemployed means one is in fact unemployable.

This may arise from a normal human reaction to hearing bad news. We look for a reason that makes the bad news make sense. Somehow, the theory goes, we live in a rational world, and in a rational world, the person who is unemployed must have done something wrong. In this way, unemployment becomes comprehensible – and then we can stop worrying about it or fearing that it will happen to us. At our neighborhood block party this summer, a neighbor remarked that his company had come through the worst of the economic crisis well. I asked him about job cuts, and he smiled. “Well, those who needed to be cut were cut, and those who were supposed to keep their jobs, kept them. We are a stronger company for it.” People around the table nodded – and any disagreement was kept quiet in this public context. While the man who spoke may have not been aware, at least three of those at the table had lost jobs in the last year and were struggling to hold onto their homes on our block. The speaker had made the job losses at his company make sense to the point that he was unaware of the pain of those at table with him.

It is crucial that we in the community of faith do not mistake the world for a place that makes sense, is rational, or is making good decisions that offers people the treatment they deserve. We must recognize that there is another ethic, another logic, another more compelling and true narrative, to which we are called to proclaim and live out. In a time when political rhetoric suggests that those who are not rich are to blame for their condition; when those who occupy wall street are called un-patriotic, as the wealth of Wall Street is “the American way”; and when “class warfare” has come to mean “expecting those who are richly blessed economically to take part in lifting the rest” – we are called to proclaim something different. It is crucial to remember that we who follow Jesus are called to remember and abide by a different, counter-cultural narrative. This means, in part, understanding and proclaiming that people who are poor are not persons of less intrinsic worth; that government has responsibility for alleviating poverty and suffering, and believers have responsibility to call on the government to do just that. A Christian understands that the government is one tool by which God’s work gets done. Regarding poverty, the government can be a very effective tool to increase or decrease suffering, and believers must call on the government to take part in the decrease of suffering and the increase of quality of life for all.

- As people of faith, we must remember that it is only because God gives us the capacity to feel for others whose situation does not mirror our own that those who are not poor are able to feel for those who are poor and thus to be moved to reach out in efforts to alleviate suffering and increase the quality of life for all. In Caritas in Veritate, Benedict points out that while the forces of globalization make us neighbors (that is, we live in more proximity to more people who hail from more diverse regions of the world), it doesn’t make of us brothers and sisters. This comes from God, who loved us first and taught us how to love, and from Jesus, who leads us to see Christ in every person we encounter.

For too many believers and too many congregations, the realization that we are family with those who are at a different economic level than we is difficult to imagine, integrate, and act upon. Congregations tend to be economically homogenous (although this has in many ways broken down, often in hidden ways, during the current recession). People who cannot find a way to fit in either don’t come or stop coming when their circumstances change. God has given us the ability to love, and often our hard hearts make it difficult to act on this gift. We are called to do better, particularly as the crisis continues.

Finally, there is the issue of sin. Many who are not poor have vested interests in the economic status quo. This is a very hard issue to engage in conversation in many congregations. Pastors, leaders and members of congregations are called by the urgency of the present moment to step up and lead reflection of the ways in which wealth for some is founded on the poverty of others, and to call for repentance and constructive change.

- Finally, as many congregations embark on a season of stewardship, there are appropriate thanks given to God for all we have an all we are. We often forget where we got what we have, and begin to believe ourselves deserving of the stuff we “own”. My favorite economist, Amartya Sen, came up with a nifty acronym for the feeling we have for those things that have come to us through unmerited grace, power and privilege. Sen calls this “evasion”:

- E – Entitlement

- V – Valid for

- A – All the

- S — Stuff

- I — I

- O — Own

- N — Now.

We have to get off the “evasion” bandwagon and remember who and whose we are, and whose all the stuff we “own” is too. We cannot evade this truth or our responsibility to steward what we have faithfully, making use of God’s gifts in ways that make life possible for not only ourselves and those we love but for others whom God puts in our path as well.

We have also been given three precious gifts that can help us counter our human tendency to put our heads in a hole and ignore the sinful reality in which we live, which is robbing life, health, and humanity from so many. Thanks be to God for these gifts!

- The gift of Love, which has the power to cast out fear, a potent force when issues of money arise in the Christian community.

- The gift of Good, unquestionably stronger than evil, and which raises us to the place where we can be informed by our better angels in the work of change, inside congregations, in communities, and nationally and internationally.

- And the gift of Life, which overcomes death, a gift given to all the creatures of God.

The countercultural, counter-intuitive nature of these truths can make us quail at the thought of proclaiming them in a society that understands the opposite of the good news Jesus calls us to bring. But these are the only truths on which a new reality can be built. Ultimately, these are the only truths that are actually true. May we look to God for the strength and wisdom to offer a reality that is real, compelling, and life-giving in a context where poverty and its attendant ills of fear, evil and death continue to flourish.

Read Leslie Woods’ Essay, “Poverty in America and What the Church Can Do”

Read Karen Keene’s Essay, “Poverty in America and What the Church Can Do”

We went to see the movie Margin Call yesterday – about the “addictive” greed on Wall St. – great cast: Kevin Spacey, Paul Bettany, Demi Moore, etc – The villain/hero (the Bank’s CEO) arrives by helicopter, in the wee hours of the night, before he unleashes a “blood-bath” into the trading day. This CEO is played by Jeremy Irons who explains why he gets “paid the big bucks” even though he doesn’t really work hard. There’s no action in this movie, but it was at the same time, a gripping film. I found it to be the most effective film on the greed and meltdown that has brought America to its knees because there was no hype – there is no need to hype this story, just show the greed. In any case, bringing it back to poverty and the no-house people, at the end the CEO gives the Kevin Spacey character his personal philosophy and justification about the business they are in (raking it in, in obscene amounts). He says in human history, there have always been people like them who sit at the top – today, he admits, there are “many more of us” than centuries ago, but for the group at the top, the percentages never change: Yes, there is always the 1% who will lord it over the rest of humanity – that’s just the way it is, and that’s just the way it always will be…. so are you in or out? In a very real way, the film lays bare how empty and depraved this top 1% is. Go see the film – it just opened!

Thanks — read a review of it on a plane this week and want to see it!

Your story reminds me of an experience I had back in the 80s when I took a South African to the southside of Chicago. He had no idea just how much America is not the country it thinks that is. How little has changed since then.

I pray for all the no-house people of America and the whole world.

Amen!