The Role of the Church as the Climate Changes by Cynthia Holder Rich

It’s the rainy season in Tanzania. We live in the northern part of the country where Mount Meru forces rain much of the year (and at about 20’ shy of 15,000’, the amount of rain forced is significant). We have some rain in most months of the year, so we didn’t know what to expect when the “real” longer rainy season (March-May) began.

It’s the rainy season in Tanzania. We live in the northern part of the country where Mount Meru forces rain much of the year (and at about 20’ shy of 15,000’, the amount of rain forced is significant). We have some rain in most months of the year, so we didn’t know what to expect when the “real” longer rainy season (March-May) began.

Now, as we have learned, there’s a reason they call this the “rainy” season. At this point, the rain has been coming steadily for hours every day (and often, every night) for months. At our house, this means that our clothes, which dry on a line on the back porch, are generally damp when we put them on. There is always some mud on the floor, no matter how much cleaning happens. Mold might be found on cloths left too long on tables. And salt, no matter what tricks we play to keep it flowing, has to be dispensed with spoons or fingers. It simply will not come through the tiny holes. The air has been much too wet for much too long.

We’re grateful for the rain, despite the inconveniences. This heavy rainy season—which locals call “normal” – is the first “normal” rainy season the area has experienced in a decade. This is because the climate is changing – indeed, it has already changed and the changes keep coming.

We’re grateful for the rain, despite the inconveniences. This heavy rainy season—which locals call “normal” – is the first “normal” rainy season the area has experienced in a decade. This is because the climate is changing – indeed, it has already changed and the changes keep coming.

Yes, I know. People in other areas of the world fight and debate and make decisions that impact people around the globe based on disagreement on this central concept. To say that the climate is changing or has changed is deemed “political” in some places, and pastors being “political” might result in their termination. Just ask Father Patrick Conroy.

In Tanzania, however, there is neither fight nor debate. It is not considered “political” to see, or to note, the changes in the climate. Because Tanzanian people–the entire society, and much of the economy–live close to the land, the fact that the weather has changed is not in doubt. Everyone in Tanzania knows that things have changed, and that many negative impacts have come along with the changes. Everyone knows, and no one disagrees.

As we prepared to move here, we both did some reading about the country, the people, the geography, the animals, and what challenges Tanzanians are facing. Climate change was on the list of issues that emerged, so we knew that was one challenge our future students would be confronting. At Christmas, we travelled outside the rain zone of Mt. Meru and saw how very few kilometers’ drive it took us to arrive in a much dryer landscape, with much less vegetation to feed people and animals.

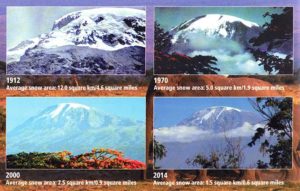

Besides agriculture, another main economic driver for Tanzania is tourism. Tourists become aware of climate change, too – mainly through their views, and their comments upon, the snowcap on Kilimanjaro, and on beach erosion, and the number of animals seen in places like the Serengeti–and how these have changed over the years. Tourist raves and complaints on TripAdvisor and other websites drive how many visitors come, so keeping tourists happy in a context of climate change has become a governmental concern. This is challenging, as all of these are impacted by rainfall amounts, which the government cannot control.[1]

Besides agriculture, another main economic driver for Tanzania is tourism. Tourists become aware of climate change, too – mainly through their views, and their comments upon, the snowcap on Kilimanjaro, and on beach erosion, and the number of animals seen in places like the Serengeti–and how these have changed over the years. Tourist raves and complaints on TripAdvisor and other websites drive how many visitors come, so keeping tourists happy in a context of climate change has become a governmental concern. This is challenging, as all of these are impacted by rainfall amounts, which the government cannot control.[1]

At Tumaini University Makumira, our Tanzanian students come from every part of the country, so have grown up with a variety of experiences of climate change. This semester, I am teaching Missiology and Ecumenism. Just like every other course we are teaching this year, this is a “new prep” for me – every class session has to be newly-created. For one class session, I decided to try writing a case study[2] based in experiences familiar to the students in the class. This is an approach that has some risk attached for instructors who’ve been in the country as short a time as we—so might get the particulars in the case wrong.

In the case, there was a pastor, grateful to be called to a congregation of devoted and active people in a small village. The village also featured a mosque, a large and growing Pentecostal congregation, and a traditional healer whom many people in town respected and consulted. Tension, and competition, had grown between these religious leaders.

Everyone in town was also impacted by climate change–the rains had not come at all last year and they were late, and light, this year. Last year, people had less money, so giving to the church decreased. A substantial number of people in town began to experience hunger, and the pastor preached about the need to pray for and serve those in need. The sermon elicited no response—except for the visit of some wealthy members, who shared that pastoral energy should be put toward caring for the congregation rather than getting involved in caring for others.

This year, hunger is worse. Some people are in serious need. The diocese called, asking for an increase in giving, as other congregations had decreased their pledges. The church treasurer stopped by, stating that the congregation’s budget would have to be adjusted, and the pastor’s salary was probably going to be cut. And the leader of the women’s organization came, with much enthusiasm for the congregation taking a leadership role in gathering all religious organizations to develop a community-wide strategy to address hunger in town, and to work toward the development of a better future for all.

The case study evoked laughter and much deep discussion. Small group reports focused on a variety of cogent issues relating to ecumenical mission—gratifying to this teacher, as I’m always happy when my teaching leads students to make informed connections. In the large group discussion, I asked if they had experienced changes in the climate like those described in the case. Responses from every corner commenced, of “yes!”, “it’s very common!”, “so often”. So I asked, “What does climate change mean to you?”

“It means death”, stated one student.

Struck, I said, “Say more.”

“It means that people get sick”, said one. “It means more people are poor”, said another. “It means that people leave villages and move to cities”, said one. “Yes, and that means there are fewer people to care for the elderly and the sick”, shared another.

So I asked what for me is a constant in class: “What is the role of the church?”.

This month, people in many countries celebrated Earth Day, a day to remember the Earth and its gifts to us all, a day that has become part of the annual rhythm for a growing number of people around the world since it began in the early 1970s. The March for Science also took place this month, gathering people in many communities to stand up for scientific findings and the scientific method of developing learnings and understanding “truth” about the world.

And this month, Scott Pruitt, US Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency, testified before US Congressional Hearings. Mr. Pruitt has led the Agency for 14 months and change. In that time, the EPA has de-emphasized science—particularly scientific findings on climate change—and Mr. Pruitt recently suggested that climate change might be a good thing. Pruitt promotes a “pro-business and pro-environment” stance, deemed by many in the scientific community as aspirational and inaccurate. However, that inaccuracy is only problematic if you believe in science.

And this month, Scott Pruitt, US Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency, testified before US Congressional Hearings. Mr. Pruitt has led the Agency for 14 months and change. In that time, the EPA has de-emphasized science—particularly scientific findings on climate change—and Mr. Pruitt recently suggested that climate change might be a good thing. Pruitt promotes a “pro-business and pro-environment” stance, deemed by many in the scientific community as aspirational and inaccurate. However, that inaccuracy is only problematic if you believe in science.

Or, if climate change means death to you.

A recent review of 50 peer-reviewed[3] articles on climate change in Tanzania found that changes in the climate have resulted in extreme drought, crop reductions, extreme flooding, greater temperature swings and a greater number of temperature extremes, increased food insecurity, increased outbreaks of infectious disease—especially diseases that are insect- or water-borne, and increased loss of life through disease, hunger, malnutrition and starvation. Authors recommended the building of increased infrastructure for irrigation (which brings its own problems, as they admitted), and a great increase in government and other budgets in the health sector.[4] From whence the money is to be procured is not discussed in the article, but other tables would surely have to take this up.

In a time of increased climate change and decreased funding for mission, What is the role of the church?

In a time when many in the US—including many Christians—deny climate change and scientific findings about it, What is the role of the church?

In a time when the church is encouraged to “not be political”, What is the role of the church?

We who follow Jesus spend most Aprils, and this one too, in the Easter season. This is the time in our faith walk when we focus on new life—resurrection—love coming again like wheat gloriously springing forth green.[5] This is the time when Tanzanian brothers and sisters in Christ, who begin most every sentence with Bwana asifiwe! (Praise the Lord!), pray for rain—just enough, not too little and not too much. They pray, for without rain, or with too much rain, death will surely come. We who follow Jesus believe in life, which Jesus came to bring in abundance (John 10). Following this one surely calls us to seek ways to work toward life for all, and that in abundance. How do we promote life? How can we support those whose life is vulnerable and at risk?

In this Easter season, we are called to cast out fear and act in love, courageously and joyfully serving those in need who wear the face of Christ. As the changing climate has put these at risk, we who have been blessed with safety, strength, and resources must seek to protect and defend the earth, our home, so that all may receive life in all its abundance, just as Jesus promised. May we do so, not counting the cost.

[1] We encourage those that visit us to read up on American Lutheran Rick Steves’ understandings of travel and tourism. Check out his top ten tips here.

[2] While lecture is the assumed method of teaching here, I lean on instruction I have received, primarily from my Mother, Ellagene Morgan Holder, and my professors at Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary, Drs. Linda Vogel and Jack Seymour, in developing more interactive ways of teaching and learning. I thank God for them all.

[3] Peer-reviewed is the gold standard for academic writing – if an article is called “peer-reviewed”, it has gone through a process of three or more academics in the research field of the article reading, commenting on, and approving its findings before it is published.

[4] Ojiji, Frederick et al, “The Impact of Climate Change on Agriculture and Health Sectors in Tanzania: A Review”, in International Journal of Environment, Agriculture and Biotechnology, vol. 2 issue 4, July-August 2017, 1758-1766.

[5] Text from “Now the Green Blade Riseth”, by John MacLeod Campbell Crum (could he be any more Scots??? Now there’s a name to make a Presbyterian heart’s sing.)